Bridging the Gap: Capitalized income in real estate and business valuation

Canadian Property Valuation Magazine

Search the Library Online

By Alisa Zorina, P. App., AACI, MBA, CPA, CA, CBV, CFF, Principal, Zorina Consulting Ltd.

It is common for small and medium-sized private businesses to operate out of a real estate asset that it owns, whether that be a residential home converted to offices or a specialized industrial facility. As a result, real estate appraisers and business valuation practitioners commonly intersect when carrying out litigation support, tax planning support, certain commercial appraisals, and related consulting assignments. The practitioners from both professions speak the same language: net income, fair market value, etc. The similarity, however, ends at terminology.

Net income in real estate represents stabilized income less stabilized expenses; that is not what a business valuator thinks when they use this term. Net income in valuation is equivalent to accounting net income and represents what remains of incurred and accrued revenue after all incurred and accrued expenses, including income taxes. The result is that a cash flow measure before taxes (net income in real estate) and an accounting accrual-based after-tax measure (net income in business valuation) are both known as ‘net income.’

Comparing and contrasting definitions is a start, but at the heart of the divide between real estate and business valuation is how each profession approaches the assignment.

A real estate appraiser values the real estate asset, while a business valuation practitioner values the concert of assets that generate value. Real estate may be a part of that concert, but there are also other tangible and intangible assets such as brand, patents, customer lists, and operational know-how that help a company generate income — and, in some cases, more or less income than competitors with the same assets.

It is exactly because the real estate appraiser’s mandate is to value the asset that they do not become entangled in the web of tax structures. The value of a business, on the other hand, is exchanged through the purchase and sale of company shares. A business valuation practitioner must therefore consider the impact of corporate taxes and corporate structure before arriving at the value of a given company’s shares. The mandate to value a company’s assets — rather than its shares – is what drives real estate appraisers to operate on a pretax basis and business valuation practitioners to operate on an after-tax basis.

The impact of this distinction is most apparent when looking at the capitalization approach used by both professions. While both professions recognize that the value of an asset or a business can be predicated on the income it generates, there exists a subtle, but significant difference that goes beyond taxes and corporate structure.

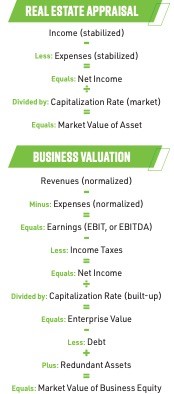

Recall that, in real estate appraisal, direct capitalization consists of taking income and expenses that are stabilized and dividing this by the capitalization rate to arrive at the market value of an asset. In business valuation, revenues and expenses are normalized, reduced by tax, and divided by the capitalization rate to arrive at the enterprise value, to which a business valuation practitioner will add redundant assets and deduct debt to arrive at the market value of business equity.

The subtlety is not in the capitalization rates, debt, or redundant assets: those differences are apparent. The subtlety is in the mechanics of stabilization versus normalization between the two professions, and while the terms may sound similar, that is where the similarity ends. While both professions review past performance to identify non-recurring blips that need to be adjusted to arrive at what a typical operating year looks like, appraisal professionals can do something that business valuators cannot.

Specifically, appraisers can stabilize income (and expenses) by adjusting the financial performance of the asset to market terms. For example, if the owner of an asset entered into a lease agreement where the renter pays below market rent, an appraiser will reflect the impact of the unfavorable terms for the duration of the lease, then assume that the asset will revert to market terms under the next owner.

Doing this makes sense in the context of valuing an asset; we assume the next owner of the asset will be an informed market participant that will not make the same mistake as the current owner. On the other hand, a business valuation practitioner cannot ‘adjust revenue to market’ when valuing a business and the normalizing adjustments to revenue, if any, will be tied to historic operating performance.

To demonstrate the impact of not being able to ‘stabilize to market’ like an appraiser, imagine a scenario where a business valuator would review a plastic surgeon’s financials and conclude: “Dear surgeon, you are not very good at running your business – let me ‘stabilize’ your revenue based on what your (more successful) peers are earning in the industry.” The resulting value would not be the value of that specific surgeon’s business and the business valuators mandate would not be fulfilled.

Being clear on the appraiser’s mandate to value the asset and the business valuator’s mandate to value the business becomes critical in engagements where the line between assets and operations blurs. Understanding the distinct lens with which each profession views these engagements can help both professions bridge the gap to consistent valuation conclusions.