Public Sector Buildings: Valuing Forgotten Infrastructure

Canadian Property Valuation Magazine

Search the Library Online

Methodology to recognize extraordinary deferred maintenance in asset valuation1

By Bruce Turner, MBA, AACI, P. App., president of Heuristic Consulting Associates (HCA) in Courtenay, BC; and Robert Metcalf, a professional appraiser and senior consultant with HCA

Reprinted with permission of International Association of Assessing Officers from Fair & Equitable, March 2015, Volume 13, Number 3. Copyright Ó 2015

Introduction

Problem and opportunity

Once proud symbols in local communities, many public sector buildings throughout the Western World are in a state of disrepair. Some of the reasons for this are summarized as follows by the Business Council of British Columbia (BCBC):

Many observers argue that governments in advanced countries often are not well placed to meet growing and increasingly complex infrastructure needs. A major impediment is constrained public budgets, which have been the traditional source of most infrastructure finance. Population growth, an aging population, increased urbanization and congestion, escalating demands for healthcare and other services, slow economic growth, and environmental issues are all straining government resources. In the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis and great recession, fiscal prudence has become a dominant focus for most governments across Canada.

Adding to the complexity of financing projects is the fact that voters seem increasingly reluctant to pay higher taxes or fees. If the value of an investment is evident, citizens may be willing to pay more, but the value proposition must be clearly articulated to secure public support. – From BCBC’s white paper on Infrastructure Policy & Financing – October 2014.

The problem with public sector buildings is widespread, as the inset comments below demonstrate:

An anecdotal description of extraordinary deferred maintenance

A ceiling collapses in a fine arts studio, forcing its closure just two weeks before exam time. Water leaks in a chemistry lab, ruining both the experiment and the equipment. Classes are cancelled for hundreds of students because of excessive heat.

- Deferred maintenance: “a ticking time bomb” in the public sector –

- “A problem that is easy to ignore until something breaks… “

Time and again, maintenance and repairs are deferred to yet another budget cycle, and the backlog of deferred maintenance builds. http://www.cou.on.ca/publications/reports/pdfs/campus-in-decline-november-2004

“In Europe, universities have become near slums as administrators have skimped on facilities.” – The Global Race to Reinvent the State. J. Micklethwait & A. Wooldridge.2014.

Recent research shows that many real estate investment managers would be reluctant to even consider purchase of a property that had been allowed to deteriorate to an extraordinary degree. The reinvestment required and the greater uncertainty introduced by extraordinary depreciation increases portfolio risk such that qualified purchasers dismiss the property in favour of candidates in better condition. Developers also look at such deteriorated property for re-development potential and severely discount current improvements.

Dealing with extraordinary depreciation is not a new problem for appraisers. But it is one where information to aid analysis hides in plain sight, lacking consistently applied methodology for appraisers to enhance their client’s or employer’s decision making.

So, how might appraisers use information like condition reports and related metrics that are now commonly available to value extraordinarily deteriorated buildings? Is extraordinary deferred maintenance best recognized in Ouija board adjustments, or might appraisal judgment and bootstrapping be more evidence-based?

This article explores the opportunity for more supportable, evidence-based appraisal judgment versus the temptation of resorting to ‘Ouija board’ value conclusions. That is, helping to ensure that appraisal judgment is rooted in sound market analysis, while building upon proven valuation methodologies.

The idea for the article arose from a consulting assignment to review the assessments of government owned buildings, where reactive maintenance strategies over many years had left high-profile buildings in a deteriorated state with diminished service life and thus reduced asset values. This situation, combined with the assessor’s constant challenge to allocate thin resources to address increasing performance requirements, often means that reduced asset values are not necessarily recognized in periodic property assessments for public sector buildings. It also means that extraordinary deferred maintenance and reduced building stewardship can actually be more costly to taxpayers over the longer term.

RESEARCH APPROACH, METHODOLOGY and CONCLUSION

Research for the consulting assignment first required clarifying the problem, i.e., first understanding the context described above. Then defining extraordinary deferred maintenance (EDM) to describe and develop a methodology based on appraisal principles that facilitated the appraiser’s interpretation of market behaviour in consistently recognizing any loss in value.

Carefully considering guiding appraisal principles and concepts2, research needed to validate the methodology against market behaviour, and allow comparison to current practice.

Research included three concurrent phases:

- Validating the proposed methodology with the experience and practices of real estate investors and senior decision makers.

- Exploring the current practice of leading assessment agencies.

- Completing an extensive literature review.

The research questions to answer included:

- Does the proposed methodology to recognize EDM reflect the behaviour of real estate market decision makers?

- Can the appraiser rely on facilities condition assessment (FCA) reports and facilities condition indices (FCI) to aid appraisal judgment and achieve more accurate, equitable and evidence-based valuation conclusions?

- Based on the authors’ research findings, both questions may be answered in the affirmative.

Based on the authors’ research findings, both questions may be answered in the affirmative.

WHAT IS EXTRAORDINARY DEFERRED MAINTENANCE?

“It is unwise to pay too much, but it is worse to pay too little. When you pay too little, you sometimes lose everything because the thing you bought was incapable of doing the thing you bought it to do.”

John Ruskin (1819-1900)

Based on the comprehensive research for this project, the authors developed the following definition for extraordinary deferred maintenance (EDM).

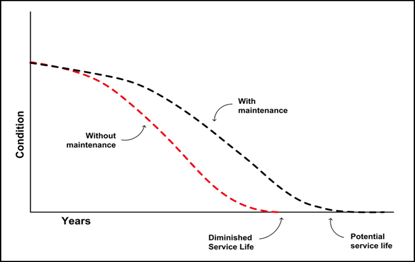

EDM exists where a building – in its highest and best use (HBU) – shows greater than normal maintenance deficiency, requiring corrective action to satisfy the generally expected level of building functionality, utility or performance. EDM is more likely found where owners elect ‘reactive maintenance’ or ‘crisis response’ maintenance strategies. That is, choosing failure replacement over preventive maintenance strategies. EDM reduces the asset’s (or component’s) service life and, thus, its value (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: EDM Reduces Service Life

Diminished service life – or increased effective age – is evident in the condition, quality and utility of a structure. The impact on asset value is based on an appraiser’s judgment and evidence-based interpretation of market perceptions. The varying maintenance strategy and standards of owners and occupants can influence the pace of building depreciation. The effective age estimate considers not only physical wear and tear, but also any loss in value for functional and external considerations.3

MEASURING THE IMPACT OF EDM ON ASSET VALUE

The premise for measuring EDM is straightforward. The asset, i.e., the entire building or some component, is deteriorated beyond its normally expected condition/utility – in comparison with typical market or expected asset performance level – to such an extent that a potential purchaser/investor would reduce their offer price, based on the principle of substitution.

The test for EDM involves comparing ‘observed condition’ of the subject property against the normally expected condition (level of depreciation) that represents the ‘standard of care’ for a similar asset in its comparable market set.

Before discussing ‘standard of care’, it is useful to review Facilities Condition Assessment (FCA) and introduce the Facilities Condition Index (FCI).4

WHAT IS FCI5?

Facilities Condition Assessment

FCAs provide important information and have become commonplace in CRE transactions and portfolio investment decisions. As part of disclosure during transactions or to expedite the sale of assets, vendors often provide qualified purchasers with comprehensive condition assessments.

Professionally prepared FCA reports provide a benchmark for the building’s relative performance and prioritize projects for maintenance, repair or renewal. They provide defensible cost estimates that the decision-maker can rely upon to make real estate acquisition, reinvestment or disposition decisions.

The FCA report provides information about the current condition of building components (such as roofs or boilers) expressed as statements about deferred maintenance, or ‘catch-up’ costs. They may include information on ‘keep up’ costs, which are forecasts of future lifecycle renewal requirements, or optionally ‘get ahead’ costs – identifying opportunities for facility adaptation and improvement.

The methodology in this article focuses on ‘catch-up’ costs.

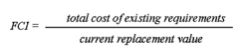

Facilities Condition Index

The FCI (an optional provision in an FCA report) is a key building performance indicator used to objectively quantify and evaluate the current condition of a facility to make benchmark comparisons of relative condition for that building with its comparable set (inclusive of private and public sector buildings).

The FCI is an industry standard method for comparison of relative asset conditions, expressed as a formula (US Federal Real Property Council, 2008):

The test for EDM involves comparing ‘observed condition’ of the subject property against the normally expected condition (level of depreciation) that represents the ‘standard of care’ for a similar asset in its comparable market set.

Before discussing ‘standard of care’, it is useful to review Facilities Condition Assessment (FCA) and introduce the Facilities Condition Index (FCI).

FCI Condition Scale

The lower the FCI, the better condition the building is in. Current industry benchmarks indicate the following subjective ratings6:

| FCI | Condition |

| 0-5% | Good |

| 5-10% | Fair |

| 10-30% | Poor |

| >30% | Critical |

‘Catch-up’ costs7 reflect deficient conditions that are typically derived from an FCA8 report carried out by an experienced and qualified team of professionals (e.g., architects, engineers). The FCI provides a relative measure for comparing the condition assessments of many buildings, and for determining the most important priorities to address in capital expenditures.

The identified ‘catch-up’ costs provide the information base for determining any value adjustment for EDM.

The appraiser may also interpret the prioritized ‘catch-up’ costs in the FCA report, reflecting on how these may be typically considered by investors in market transactions.

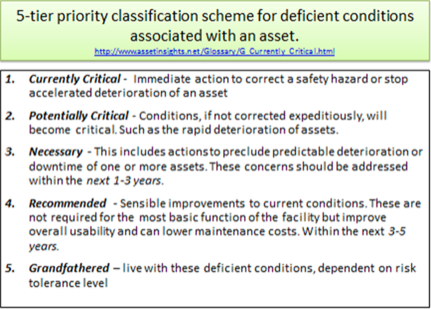

Industry standard priority classification for deficient asset conditions

Catch-up costs in an FCA report are ranked in a five-tier priority classification scheme, as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Industry Standard Priority Classification for Deficient Asset Conditions

A word of caution: In interpreting FCI information from an FCA report, the appraiser needs to ensure a clear understanding of the FCA report’s terms of reference and underlying assumptions. For example, FCI benchmarks may be for different periods – the cost requirements may reflect one-year cost requirements, five-year cost requirements, or whole-life cost requirements.

OBSERVED VS. NORMALLY EXPECTED CONDITION

To identify the existence of EDM, an appraiser needs sufficient knowledge of the market to first determine the normally expected condition for the subject property’s comparable market set. This determination is facilitated through review of a professionally prepared condition assessment report.

The subject building’s ‘observed condition’ can then be determined – applying appraisal judgment that is supplemented by information from the FCA report and confirmed through the appraiser’s physical inspection of the property.

Comparative FCIs assist in distinguishing the subject’s observed condition from that normally expected condition in the comparative market set. To do so, it helps to identify the owner’s maintenance strategy with the ‘standard of care’ that is typical to the property type and its market.

STANDARD OF CARE AND EVIDENCE OF OWNER’S MAINTENANCE STRATEGY

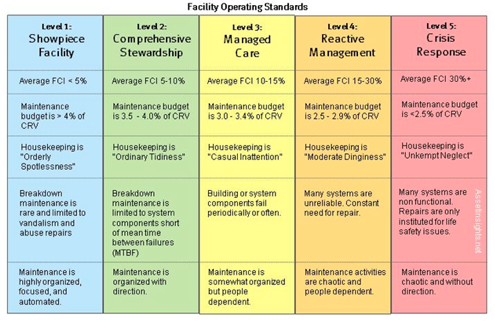

For various reasons, building owners may elect a maintenance strategy to reflect a ‘standard of care’ that ranges from ‘showpiece facility’ to ‘crisis response.’9

Where that maintenance strategy is reactive and where funding levels are reduced, the normally expected standard of care for the comparable property set (or market) is not met. In such circumstances, it is more likely to find that EDM affects the building’s service life and thus its value.

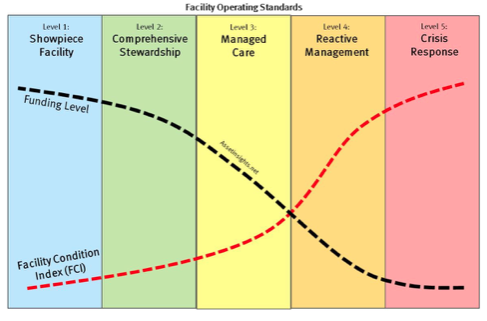

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between maintenance funding levels and FCI.

Figure 3: Funding Levels and Maintenance Strategy

‘Cost-to-cure’ or catch-up costs are intended to shift ‘standard-of-care’ to the left in Figure 4. For example, the cost requirements in an FCA report might be targeted to shift an indicated Level 4 (Reactive Management) FCI of 15-30% to a Level 3 (Managed Care) FCI of 10-15%. Presuming the Managed Care target level is the normally expected condition in that asset category, the appraiser would adjust for EDM cost requirements and then apply the appropriate, validated age-life depreciation table in concluding a value estimate – taking care not to double count on depreciation allowances.

Figure 4: Descriptions of Five Operating Standards

METHODOLOGY TO GAIN CONSISTENCY IN PROCESS; UNIFORMITY IN RESULTS

Depreciation is the loss in value due to any cause – the difference between an improvement’s market value and its replacement cost new.

Review of current practice shows a number of issues that need to be addressed to achieve accurate, equitable value estimates.

Mass appraisal techniques in applying the cost approach may not recognize EDM for various reasons. For example, modeling based on typical age-life depreciation tables that may ‘arrest’ depreciation at some pre-determined level are unlikely to capture the severe loss in value evident in many special purpose public sector buildings today.

Also, whether for single property or mass appraisal, it is not uncommon to find that age-life depreciation tables have not been validated in local markets.

In applying the income approach, modeling that reflects the provision for typical structural reserves and capitalization in perpetuity is unlikely to sufficiently recognize the ‘critical’ (or even ‘necessary’) cost requirements for replacements and renewal of building components identified in an FCA report.

The following sections describe methodologies for both the cost and income approaches to provide evidence-based loss in value due to EDM using FCA and FCI information.

Quantifying the Impact on Value of EDM

Example processes for identifying and quantifying EDM adjustments (using either the cost approach or income approach) are presented as decision trees in Appendix A and B.

These decision trees are presented as scenarios, where the appraiser is asked to review a valuation (either during pre-roll consultation, upon appeal or as part of a consulting assignment) where EDM is believed to require recognition.

After considering highest and best use (HBU), an adjustment for EDM reflects a loss in building value – measured as the present value (PV) of the difference between value under normally expected maintenance (or ‘standard of care’) for the asset, and value in its current ‘observed condition.’ It is a measurement of the loss in value due to reduced service life of the entire asset or of its components.

The following section provides background to enhance understanding of the decisions and processes implicit in the decision trees. The premise for EDM adjustment is similar for special purpose and market properties, but the process varies according to steps appropriate to the valuation approach (i.e. cost or income).

Special Purpose Property (COST APPROACH):

We begin by considering EDM for a special purpose property – using the cost approach to value.

- Premise for EDM: The premise for EDM is straightforward. The asset (i.e., entire building or some component) is deteriorated beyond its normally expected physical condition or functional capacity within its comparative market – to an extent that a potential purchaser/investor would reduce their offer price, based on the principle of substitution. The test for EDM involves comparing ‘observed condition’ against the normally expected level of depreciation for the asset.

- Observed condition10 vs. comparable property set condition: The overall process for quantifying EDM is also straightforward. The appraiser assembles all available information, including an FCA report completed by a qualified professional team and with a physical inspection of the property, concludes an ‘observed condition’ for the subject building.

- Analyze HBU: The appraiser then completes an HBU analysis. If the current property use is not the HBU, the appraiser values the site at market and attributes a residual, nominal or no value to the building.

- Test correctness of current replacement cost new (RCN): If the existing use is determined to be the HBU, the appraiser continues to determine whether the building inventory is current and accurate, and that the RCN is correct, i.e., no adjustment should be made from the wrong starting point.

- Estimate typical replacement cost new less depreciation (RCNLD): Apply the normal depreciation allowances for the asset category/type and condition/quality to determine pre-EDM RCNLD

- Is there evidence of ‘reactive maintenance’ or ‘crisis response’ maintenance strategies, i.e., failure replacement strategy for the subject vs. preventive maintenance strategies in the comparative property set? One test for this is to consider whether the indicated depreciation (typical RCNLD) is less than that indicated by the FCI (see definition in glossary) in the FCA report?

- Assessable components: The FCA report may include items such as furniture, fixtures and equipment (FF&E) that are not assessable. Adjustments for EDM should reflect those items that are included within the definition of ‘improvements,’ as set out in the relevant statute.

- Determine EDM adjustments according to the industry standard priority ranking for deficient conditions (refer to the five-tier priority classification for deficient conditions).

- Current/potential critical rankings 1 and 2: Assuming ‘observed condition’ (supported by FCI comparison) indicates greater deterioration than normal deprecation (indicated by benchmark FCIs or appropriate age-life table), use the FCA report to identify and adjust for current and potential critical components replacement. Critical items are identified as needing immediate replacement so that the adjustments are most likely $ for $ (i.e., not discounted).

- Avoid duplication in rankings 3, 4 and 5: Adapting the discerning eye of a potential investor, identify those items that represent required capital expenditures over the next five years. The indicated replacement requirement may need to be discounted to avoid duplication and to reflect present value. The appraiser may calculate the adjustment by either:

- Discounting to PV: For components that require future replacement (e.g., within next five years), the appraiser should use judgment in determining whether these should be discounted to a PV, using an appropriate market discount rate

Market Property (INCOME APPROACH)

Refer to the Decision Tree in Appendix B, and to the steps noted above for special purpose properties, as those principles also apply to use of the income approach for market properties. The points below refer to considerations particular to the income approach:

- Ensure that physical and financial inventory is current and accurate for the subject property.

- Determine economic inputs (rent, vacancy and collection allowance, expense ratio, capitalization rate) for completing an income approach to value for the subject.

- Analyze for potential differences between economic inputs for the subject property and for the comparable market set.

- Identify, by priority rank classification, the FCA report components that are assessable (as per definition of “improvements” in the statute appropriate to the jurisdiction).

- Determine whether (and to what extent) replacement costs for those components that are recoverable from tenants, i.e., without affecting the property’s competitiveness, or ability to retain tenants.

- Calculate the EDM adjustments (using similar methodology to that for special purpose properties above).

- Analyze the strength of the real estate market (e.g., is it a buyer’s or a seller’s market) to determine whether the potential investor/purchase might be required to reduce expectations for ‘cost to cure’ discounts from the offering price.

- Decide whether these adjustments should be reflected as:

- lump sum adjustments, or as

- adjustments to valuation inputs, such as rental or occupancy rates, operating expenses, OCR.

- Take care not to duplicate the EDM adjustments by adjusting more than one input, unless warranted.

- Document the EDM adjustment so that future adjustments (e.g., when new capital expenditures reverse effects of EDM) are readily made, and to facilitate explanation of adjustments to property owners, tenants or taxing authorities.

CONCLUSION

As governments have grappled with challenges to finance infrastructure (including buildings) needs, real estate practitioners and their professional associations have developed concepts such as whole-life costing models and strategic asset management techniques, and have come to rely on information and metrics such as found in condition assessment reports to aid their clients’ property decision-making.

However, appraisers do not yet seem to have incorporated concepts and related information from commercial real estate’s strategic asset management into their traditional appraisal techniques –whether in single property or mass appraisal valuations.

The research upon which this article is based showed that appraisal practices and valuation accuracy can be improved by recognizing EDM, as real estate market investors and developers have come to do in their decisions. Appraisers can indeed rely on information from facilities condition assessment reports and metrics such as FCI (carefully interpreted) to bootstrap appraisal judgment in arriving at more evidence-based conclusions.

Adopting and refining the methodology described here, appraisers have the opportunity to incorporate concepts and related information from CRE strategic asset management into their traditional appraisal techniques – in both single property and mass appraisal.

The methodology developed for this research report can be helpful to inform decision-making for various purposes – whether to help ensure fair and equitable property tax (or payment-in-lieu of tax, PILT) burdens and in single property appraisal, or to aid business case development to better achieve portfolio objectives and to support property lifecycle decisions.

*See PDF for Appendixes A/B

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Asset performance state: A building’s performance state, which changes during time in service, is reflected by two different indicators:14

- The physical condition state – FCA (Facilities Condition Assessment)

- The functionality state – FPE (Functional Performance Evaluation)

Betterment: Costs incurred to improve the service potential (and life) of a capital asset. Service potential is enhanced when:

- there is an increase in service capacity;

- operating costs are lowered; and

- useful life is extended; and quality (e.g., vacancy levels) is improved.

Deficient conditions 5-tier priority classification scheme for with an asset15:

- Currently Critical – Immediate action to correct a safety hazard or stop accelerated deterioration of an asset

- Potentially Critical – Conditions, if not corrected expeditiously, will become critical. Such as the rapid deterioration of assets.

- Necessary – This includes actions to preclude predictable deterioration or downtime of one or more assets. These concerns should be addressed within the next 1-3 years.

- Recommended – Sensible improvements to current conditions. These are not required for the most basic function of the facility but improve overall usability and can lower maintenance costs. Within the next 3-5 years.

- Grandfathered – live with these deficient conditions, dependent on risk tolerance level. For example, a multi-tenant building may have asbestos contamination where the landlord addresses the asbestos contamination only upon tenant turnover.

Extraordinary deferred maintenance: EDM exists where a building, in its HBU, shows greater than normal maintenance deficiency, requiring corrective action to satisfy the generally expected level of building functionality, utility or performance.

- EDM is more likely found where owners elect ‘reactive maintenance’ or ‘crisis response’ maintenance strategies – i.e., failure replacement vs. preventive maintenance strategies (see Glossary for term definitions).

- Reactive maintenance – may be more common in owner occupied institutional buildings where the owner does not keep buildings in competitive condition. If the condition works for the owner’s current use, why spend more money.

- EDM reduces service life, i.e., where a building’s quality and condition/age reduce its performance so that it is no longer as competitive for its design purpose without major renovations and upgrading to modern standard.

Effective age: Effective age is the age indicated by the condition, quality and utility of a structure and is based on an appraiser’s judgment and interpretation of market perceptions. Maintenance standards of owners and occupants can influence the pace of building depreciation. The effective age estimate considers not only physical wear and tear, but also any loss in value for functional and external considerations.16

Maintenance strategy: A long-term plan, covering all aspects of maintenance management, which sets the direction for annual maintenance program and contains firm action plans for achieving a desired future state for the organization. [Website URL: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Maintenance_Strategy.html ] [http://www.assetinsights.net/Concepts/Replacement_Policies_All_01.JPG]

Facility Condition Index (FCI): FCI is an industry standard asset management tool, which measures the “constructed asset’s condition at a specific point in time” (US Federal Real Property Council, 2008). It is a functional indicator resulting from an analysis of different but related operational indicators (such as building repair needs) to obtain an overview of a building’s condition as a numerical value.17

Facility Operating Standards (Standard of Care): Comparison of the FCI and funding levels (see Facility Operating Standards diagrams below18) provides a basis for identifying the owner’s maintenance strategy. More importantly for the appraiser, it provides a basis for comparing the appraiser’s ‘observed condition’ against the expected market/operating standard for the specific property type in estimating effective age, as a test for Extraordinary deferred maintenance.

Lifecycle Models: The five-stage lifecycle model below is an example of a lifecycle model that attempts to capture the ‘cradle to grave’ cycle for building assets.

Observed condition: The observed condition of an asset is indicative of its chronological age and the degree of replacement of its depreciable components.

Preventive maintenance: Planned maintenance that is scheduled to sustain an asset’s level of expected performance during a prescribed lifetime.

Reactive (demand) maintenance: maintenance that is carried out either on the failure of an asset or when there is an emerging need. Sometimes associated with a strategy known as “sweating the asset,” or extracting most possible life from the asset with the least maintenance cost.

Repairs and maintenance: Any expenses incurred to keep the building competitive in the market in term of desirability and income generating capacity, or to maintain is functional utility in its designed use.

Service life: The period of time over which an asset (and its components or assembly) provides adequate performance and function. Service life is a technical parameter that depends on design, construction quality, operations and maintenance practices, use, and environmental factors. [Website URL: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Service_Life.html

Standard FCA: A Facility Condition Assessment (FCA) that has the following basic scope definition, quality definition and attributes.

It does not include:

- Seismic assessment

- Green assessment

- Hazardous materials assessment

- Functionality assessment

It includes a Facility Condition Index (FCI), but does NOT include:

- Facility Needs Index

- Functionality Index

[Website URL: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Standard_FCA.html ]

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE PRACTITIONERS SURVEYED

- Anthem Properties. Name held in confidence, Investments

- BC Housing Commission. Darin McLennan, Director, Portfolio Planning, Asset Strategies; Ron Hansen, Senior Real Estate Advisor; Ahmed Omran, Manager, Portfolio Solutions

- Beedie Investment Group. Name held in confidence, Asset Management, Vancouver, BC

- Bentall Kennedy (Canada) LP. Name held in confidence, Investment Management, Vancouver, BC

- bc Investment Management Corporation (bcIMC). Name held in confidence, Victoria, BC

- Cadillac Fairview. Name held in confidence, Investments. Toronto, ON

- First Capital Asset Management ULC. Name held in confidence. Calgary, AB

- Infrastructure Ontario and Lands Corporation (Infrastructure Ontario). Robert Prete, Manager, Valuation Services, Toronto, ON

- Ontario Pension Board (OPB), Name held in confidence, Managing Director Real Estate, Toronto, ON

- Oxford Properties Group. Name held in confidence, Investments. Toronto, ON

PROPERTY ASSESSMENT AGENCIES SURVEYED

- BC Assessment Authority. Regional managers, via BCA project team members

- Saskatchewan Assessment Management Agency. Irwin Blank, CEO

- City of Calgary, Assessment Business Unit. Nelson Krpac, City Assessor

- Municipal Property Assessment Corporation. Paul Campbell, Director, Centralized Properties – centralized team specialists: John Watling, Malcolm Stadig and Tim Brown (special purpose properties: income and cost approach applications)

LITERATURE REVIEW

- Albrice, D. An online laboratory for the development and testing of optimization strategies for maintenance and responsible stewardship of buildings. Glossary: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_0_Table_D.html

- Albrice, D. Branch, M. & Lee, T-S. Municipal Portfolio Stewardship with Limited Budgets: The Application of Matrix Correlations as a Tool to Support Resource Allocation Decisions in the Public Good. Draft Research Paper, to be presented at the Joint Conference of the Institute of Engineering Technology (IET) and Institute of Asset Management (IAM), London, UK. November 2014: http://www.assetinsights.net/Articles/IET_IAM_2014_Tool_to_Support_Municipal_Resource_Allocations.pdf

- Appraisals Directorate. Office Accommodation/Real Estate Sector, Real Property Services. Accrual Accounting and the Use of the PWGSC Book Value Calculator (BVC) for Determining Gross and Net Book Values for Opening Balances. Public Works Government Services Canada. Website URL (viewed November 7, 2014):

- <chrome-extension://gbkeegbaiigmenfmjfclcdgdpimamgkj/views/app.html>

- Association of Physical Plant Administrators (APPA). Robert Quirk – The Facilities Condition Index as a Measure of the Conditions of Public Universities as Perceived by the End Users. Facilities Manager Journal. 2006: http://www.appa.org/files/FMArticles/FM091006_Feature_FCI.pdf

- Appraisal Institute of Canada. The Appraisal of Real Estate, 3rd Edition. 2010. University of British Columbia; Sauder School of Business:

- Chapter 9: Market and Marketability Analysis

- Chapter 11: Improvement Analysis

- Chapter 12: Highest and Best Use Analysis

- Chapter 19: Depreciation Estimates

- Chapter 21: Income and Expense Analysis

- BC Court of Appeal – CA034277, Vancouver Registry (SC 500). Pacific Newspaper Group Inc. v. Assessor of Area 14 – Surrey-White Rock. 2006: http://bcassessment.ca/about/Stated%Cases/SC500.pdf

- BC Court of Appeal (CA037652) Vancouver Registry. Assessor of Area 10 – North Fraser v. Abolhassan Sherkat & PAAB. (SC531) – Key Principles: importance of evidence-based adjustments, and need for value estimates to support both HBU and existing use.

- BC Supreme Court (SC 396) – Assessor of Area 10 – Burnaby/New Westminster & City of New Westminster v. Haggerty Equipment Co. Ltd. – Key principles: Adjustment for contamination must be supported by evidence.

- BC Supreme Court 721 2002. Vancouver Chinatown Merchants Association v. Assessor of Area #9 – Vancouver. Key Principles: Equity compared to ‘similar’ properties; “investor not going to remediate a site to a level greater than is necessary to its HBU” [67].

- Campbell, A.; Whitehead, J. Making Trade-Offs in Corporate Portfolio Decisions. McKinsey & Company. September 2014. Website URL (viewed September 13, 2014): http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/Corporate_Finance/Making_trade-offs_in_corporate_portfolio_decisions

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Massachusetts State & Community Colleges. Matching Facilities to Missions: Strategic Capital Program. Report Summary. July 2003: http://www.mass.edu/forinstitutions/fiscal/documents/evakleinv1.pdf

- Council of Ontario Universities. Ontario Universities’ Facilities Condition Assessment Program -As of February 2010. Report December 2010. http://www.cou.on.ca/publications/reports/pdfs/fcap-report-dec-2010

- Del Duca, Stephen, Parliamentary Assistant to Minister of Finance, Ontario. Special Purpose Business Property Assessment Review & Recommendations. 2013. Ontario Ministry of Finance. Website URL (last viewed September 28, 2014): http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/consultations/par/spbp.pdf

- Ellingham, I. and Fawcett, W. New Generation Whole-Life Costing: property and construction decision-making under uncertainty. ISBN: 0-415-34657-6. Taylor & Francis, New York, USA. 2006

- Chapters 5 – 11: lifecycle options; evaluating options to develop, expand, switch use, reconfigure, refurbish, implement new technology

- Chapter 14: self-assessment matrix for whole-life evaluation

- Harp, R. Kymn. Due Diligence Checklists for Commercial Real Estate Transactions. November 2013. Website URL (viewed September 25, 2014): http://harp-onthis.com/due-diligence-checklists-for-commercial-real-estate-transactions/

- Hayes, B.P. & Nunnington, N. Corporate Real Estate Asset Management: Strategy and Implementation. ISBN: 978-0-7282-0573-4. EG Books, Burington MA, USA and Kidlington, Oxford, UK. 2010

- Chapter 2: Strategic alignment – Corporate real estate asset management

- Chapter 5: Performance measurement and benchmarking

- Hennessey, B.; Knowlton, A.; Salimian, S. The Due Diligence Process Handbook for Commercial Real Estate Investments. 2012

- Campbell, A.; Whitehead, J. Making Trade-Offs in Corporate Portfolio Decisions. McKinsey & Company. September 2014. Website URL (viewed September 13, 2014): http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/Corporate_Finance/Making_trade-offs_in_corporate_portfolio_decisions

- Jegher, William. CoreNet Global: Canadian Chapter: Real Estate Capital Management Strategy: Deferred Capital Maintenance & The Facility Condition Index. October 2009. Website URL (viewed October 5, 2014): http://canada.corenetglobal.org/Canadian/communityresources/blogsmain/blogviewer/?BlogKey=b37c5bbb-26ed-4797-aaed-d69e44d75dcb

- Joint Task Force of CSAO/OAPPA. Campus in Decline – A Report of the Joint Task Force of CSAO/OAPPA on the Need for Increased Facility Renewal Funding for Ontario Universities. 2004. Website URL (viewed October 5, 2014): http://www.cou.on.ca/publications/reports/pdfs/campus-in-decline-november-2004

- Mueller, Glenn R. Predicting Long-Term Trends & Market Cycles in Commercial Real Estate. October 24, 2001. Research Paper, Real Estate Department, Wharton University of Pennsylvania. Website URL (viewed September 14, 2014): http://realestate.wharton.upenn.edu/research/papers/full/388.pdf

- Mueller, Glenn R. Commercial Real Estate Market Cycles: How They Affect Your Local Market – US Commercial Real Estate Cycle. Franklin L. Burns School of Real Estate & Construction Management, University of Denver. 2013. Website URL: http://www.slideshare.net/CCIM/commercial-realestatemarketcycleshowtheyaffectyourlocalmarket

- Rush, S.C. and Johnson, S.L. The Decaying American Campus: A Ticking Time Bomb. 1988 APPA/NACUBO survey of capital renewal & deferred maintenance needs at U.S. colleges and universities. ISBN: 0-9113359-47-5. June 1988. Reference URL: http://www.appa.org/Research/CRDM.cfm

End notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: This report reflects contribution of many professionals (appendices). We wish to particularly acknowledge David Albrice of RDH Building Engineering and Asset Insights for their material: www.assetinsights.net Asset Insights is an online laboratory for the development and testing of optimization strategies for maintenance and responsible stewardship of buildings.

2 The methodology described later in this paper builds on the foundation principles and concepts articulated in The Appraisal of Real Estate, 3rd Canadian Edition.

3 Appraisal Institute of Canada. Appraisal of Real Estate, 3rd Canadian Edition. Sauder School, UBC, Real Estate Division. Page 19.3.

4 Observed condition: The observed condition of an asset reflects both its chronological age and the degree of replacement of its depreciable components.

5 Comments on FCA and FCI draw from material on Asset Insights: www.assetinsights.net

6 Asset Insights.net: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Facility_Condition_Index.html

7 Asset Insights: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Catch-up_Costs.html

8 Also referred to as Building Condition Assessment (BCA) reports

9 AssetInsights.net. Managed Care: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Managed_Care.html

10 The observed condition of an asset is indicative of its chronological age and the degree of replacement of its depreciable components. It is generally concluded after reviewing a Standard Facilities Condition Assessment report and following a physical inspection of the property – enabling the appraiser to interpret all information in terms of the market/comparable property set. For definition of a Standard FCA report, refer to Asset Insights URL: http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Standard_FCA.html

11 Assume that the appropriate age-life table indicates normally expected depreciation of 30% (with Managed Care), or 70% good condition.

12 The calculation would be similar to that for Rank 1 (Critical items), but for Rank 3, 4 or 5 deficient condition components, the cost-to-cure is reduced by the difference between the subject FCI and the FCI typical to the comparative property set (or asset category).

13 Assume that the appropriate age-life table indicates normally expected depreciation of 30% (with Managed Care), or 70% good condition.

14 http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Deficiency.html

http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Functionality.html

15 http://www.assetinsights.net/Glossary/G_Currently_Critical.html

16 Appraisal Institute of Canada. The Appraisal of Real Estate, 3rd Canadian edition. Sauder School of Business, Real Estate Division. Page 19.3.

17 BC Housing. Facilities Condition Index: http://www.bchousing.org/resources/Partner_Resources/Major_Repairs/FCI.pdf ]

18 Asset Insights.net: http://www.assetinsights.net/Concepts/Operating_Standard_Parameters.JPG