Stories behind the real estate

Canadian Property Valuation Magazine

Search the Library Online

There are many factors to consider in the typical work of an appraiser. Issues regarding neighbourhood, zoning and land use readily come to mind. But have you ever considered what the real estate you are appraising means to the users? Have you thought about the stories behind the real estate? In honour of Asian Heritage Month, this article focuses on three properties and how the lives of the owners were transformed, not only by the real estate, but also by their families’ journeys from Vietnam to Canada made necessary by war.

For some context, the conflict in Vietnam began on November 1, 1955, and ended on April 30, 1975, with the fall of Sài Gòn (the former name of Hồ Chí Minh City, the capital city of Vietnam). Many Vietnamese people who sided with the Republic of South Vietnam tried to escape across the seas, mainly on small river boats, risking their lives for the remote chance at a new and better future. Some survived, many did not.

Real estate story #1

Courtesy of the Nguyễn family archives.

The first location is 3388 Main Street in Vancouver. It is a 2,112 sq.ft. retail storefront being used as a restaurant in the Mt. Pleasant neighbourhood. A quick search on BC Assessment indicates that it is a strata unit built in 1997 and valued at $1,882,000. The restaurant occupying that space, Anh and Chi, was a recent recipient of The Michelin Guide’s 2022 Bib Gourmand designation and the first Vietnamese-female chef was recognized for a Michelin Bib Gourmand in Canada. I had a chance to speak with Amelie Nguyễn, the daughter of the chef and co-owner, to learn more about her restaurant and family.

Andy: Your family has a very successful restaurant, but I know life has not been easy. Can you tell us about your family’s history?

Amelie: In 1980, my parents and I came to Canada as refugees after escaping from Vietnam by boat. My parents struggled to establish a new life, with my dad delivering pizza and my mom working in a bakery. It was very different from what they did in Vietnam before the war when my father was a college instructor and my mom worked in the food catering business. They missed home greatly and used cooking to remember the smells of home. At first, they cooked for friends and then they brought their food to welcome centres in the neighbourhood. They became known as the family that cooked phở, which people wanted to eat.

Andy: Was that why they opened the restaurant?

Amelie: It was actually because they were told they could not serve food from their house because it was not allowed for health, safety and zoning reasons. In 1983, after having established a dedicated clientele, they opened the first restaurant and called it Phở Hoàng, following a tradition in Vietnam to name a restaurant according to what it served and the name of a person. Hoàng was my father.

Andy: The first restaurant was also on Main Street, but not where the current restaurant is situated.

Amelie: Our first restaurant was at 3610 Main Street, where Chef Claire’s is now. But my father wanted to offer more variety of Vietnamese food, so, in 1997, my parents built and opened the current, bigger location, also on Main Street.

Andy: Having rented your first location, why did you want to build and own the second one?

Amelie: My parents knew they were working class in Canada and understood one of the ways to build wealth was by buying land. They thought things like stocks and bonds were too abstract, unlike real estate, which is tangible. After years of saving money, they had the chance to own their restaurant space and grow the business.

Andy: How has the area evolved since 1983?

Amelie: There was not much on Main Street when we opened the first small restaurant. Even when we opened the larger restaurant, a car dealership was still across the street. But, over time, we saw hair salons, antique shops, and coffee shops, all appear in the area.

Andy: What do you think caused this change on Main Street?

Amelie: It seemed as though people were moving here from the West Side, making huge gains from selling their houses, and buying homes in this neighbourhood, which was cheaper at the time. Main Street was not as trendy as it is now.

Andy: How did the current version of the old restaurant, Anh and Chi, come to be?

Amelie: Unfortunately, my father fell ill in 2010 and my mother called me and my brother Vincent to deliver us the bad news. We were both in Australia at the time. He was in medical school, and I was defending my master’s thesis. My brother and I flew back immediately. He held on until we got home in time to say our goodbyes.

Andy: That must have been hard on your mom especially.

Amelie: She was grieving, yet still had a restaurant to run. She did not know if she could continue so my brother and I decided to honour our father by taking over the business. We gave it a modern make-over and renamed it Anh and Chi, partly because anh means older brother and chi means older sister in Vietnamese, and partly because we wanted a place that was warm and inviting, where you would want to bring your family and enjoy a great meal.

Real estate story #2

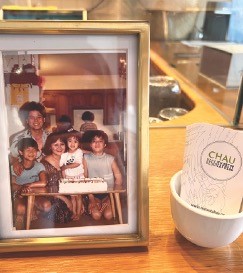

Courtesy of the Huỳnh family.

The second location is 5052 Victoria Drive, which takes us to the Kensington-Cedar Cottage neighbourhood and introduces us to Maria Huỳnh, the owner of CHAU Veggie Express. The subject is zoned C-2, which allows various uses on the dwelling’s ground and second floors. This type of use has dictated the commercial nature of Victoria Drive from about East 32nd to East 44th avenues.

Andy: I know you and your family have been in the food business for many years now, but let’s start back in Vietnam.

Maria: It all started with my grandfather who had left my dad with a tugboat. When the war broke out, my mom and dad survived by ferrying cement and gasoline for the Americans. After the fall of South Vietnam, life became increasingly difficult, and in 1979 my parents decided it was better to try to escape and risk death than to languish away in a war-torn country. It was on that tugboat that my parents made their escape. As luck would have it, eventually they were sponsored by Canada from the refugee camp on which they had landed. They were originally located in Winnipeg in 1980, but slowly moved west. I was born in Red Deer in 1981 and, in 1983, we moved to Vancouver.

Andy: How was life for your parents in Vancouver in the early 1980s?

Maria: With the language barrier, my parents did not have many options for work. My mom worked at a fast-food chain and my dad was a janitor at BC Place stadium. We were living in a housing project in Chinatown. Fortunately, my mom wanted to build a better life. She started to make meat balls in the apartment. Many of the people in the neighbourhood during the ‘80s were predominantly lower-income and of Chinese descent. They loved my mother’s recipe and would line up to purchase handmade meat balls. The orders kept coming in and soon the apartment was a small factory making meat balls and other processed meats, 24-7. It got so busy that we simply could not fill all the orders, so she saved enough money and rented a shop on Heatley at Hastings Street. Kim Chau Deli was opened in 1986. Over the years, the Vietnamese community in Vancouver had located itself along Kingsway so it made sense to be there. We lived in an apartment above the deli. We ran that for several years, but then sold the entire building with the deli as part of it.

Andy: Why did your parents want to build the next shop instead of renting space?

Maria: They decided to buy instead of rent to have better control of the lease rate. They also felt that a fixer upper would gain value over time. In the end, they sold the business for more in 2009 because it came with real estate. Another reason the business was sold at that time was my mom was having health challenges. This inspired her to do the opposite of the deli business and create one that offered plant based food.

Andy: Were you always in the food business?

Maria: I was drafted into the business from the time I could remember. Instead of playing after school, praise was given for labelling products and helping where I could. I really did not want anything to do with my parent’s business, but family is family. When I graduated high school, I did not really know what to do, but with all my related food experience, I stayed in the industry by working at the Sequoia company chain of restaurants. I learned that the industry could offer more than what my parents showed me and I enjoyed it. I took a break and travelled to Vietnam for about three months to stimulate my senses in food and culture, and to connect with my roots. It was an eye-opening experience to see the sights, hear the sounds, and taste the food I had only had at home or at other Vietnamese restaurants in Vancouver. After I came back, I decided I wanted to go into the business and enrolled in culinary school.

Andy: Did you then open CHAU Veggie Express?

Maria: I first opened a restaurant on Robson Street and called it Chau Kitchen and Bar. Looking back, that location was opened with skepticism within the Vietnamese community, however, it was a pivotal point in moving Vietnamese food in another direction. I ended up selling that business after two years because of my mother’s illness. Unfortunately, it was sold to someone who did not want to preserve what was built and who changed it all together.

Andy: What led you to opening another restaurant?

Maria: Basically, two things. One, at my condo’s concierge I overheard a lady compliment this little Vietnamese restaurant that she found quite charming on Robson near the Safeway. I turned to her and said that’s mine, but I am going to close it because it was not what I expected. It turned out she was the creator of a famous culinary school called Dubrulle and she advised me to not discount what I had learned and, if I were ever to do it again, to make it even better. And two, my mom had been diagnosed with a brain tumor and decided to switch to a vegetarian diet for the sake of her health. She wanted to give back to the community in her way by no longer making and selling meat, but focusing instead on family and health through vegetarian food.

Andy: How did you learn more about the vegetarian side of things?

Maria: I travelled to countries like India because there are places where it is illegal to eat meat. I also looked at Vietnamese vegetarian food. Đồ chay is the term we use to classify vegetarian food prepared by Buddhist monks, since it is part of their practice to do no harm to animals. I also went to stay at a Vietnamese monastery to see what they were doing. The more I learned, the more I wanted to focus on it, but with my own interpretation. In 2008, I opened CHAU Veggie Express with a vegetarian menu inspired by my Vietnamese heritage.

Andy: Is the building also yours?

Maria: It was important to own the building because it was something that potentially could be long lasting. I did not want to put in the time and effort upgrading and improving something that was owned by someone else. I also wanted to be a part of the neighbourhood and the thought of renting was too transient for me. This part of Victoria Drive has some of the best eateries in Vancouver and I am proud to help shape it.

Real estate story #3

Courtesy of Teresa Trần.

The third location is 701 Kingsway at the corner of Fraser Street. A street view inspection indicates that this is an old-style plaza with ingress and egress off both Kingsway and Fraser. It is a one-storey, multi-tenanted building set back from the small and functionally obsolete surface parking lot. This is one of the last strip plazas along Kingsway with re-development potential. BC Assessment reports that it was constructed in 1987 with an assessed value of $14,330,200, of which $14,302,000 is attributed to the land. One of the original tenants is Ba Le Deli and Sandwich Ltd. I spoke to Teresa Trần to learn more about her family business.

Andy: Ba Le has been a staple for bánh mì (Vietnamese sandwich) for as long as I remember. How did it start and when?

Teresa: It was my father who started it. In Vietnam, he was a soldier in the war on the side of the South Vietnamese army.When the communists won and were seizing assets, he knew he had to leave. His family planned a trip on boat and landed at a refugee camp before coming to Canada. That was in 1980. After about seven years, my dad opened the shop.

Andy: Why was the focus placed on sandwiches?

Teresa: We come from a long line of sandwich shop owners. I am the third generation. My father was the second. My maternal and paternal grandmothers were the first, having started it in Vietnam by operating mobile food carts. The know-how has been a part of the family for generations. We make all the products that go into the sandwiches from the bread to the meat to the mayonnaise and pâté.

Andy:There were other places in Vancouver to set up, why did he settle on this one?

Teresa: In Vietnam, people would congregate at intersections which were accessible and visible. Plus, in the 1980s, many Vietnamese people had settled around Kingsway, so it made sense for a bánh mì shop to open there. The rents were also cheap back then. There were many other Vietnamese businesses that had opened along Kingsway for the same reasons.

Andy: Was it difficult for him to get the business started?

Teresa: He knew very little English, however, since staff at the city were very helpful, he had a relatively easy time. He was able to get his business license quickly, not like it is now. Also, things such as property taxes, food and rent were much cheaper back then.

Andy: Like many other Vietnamese kids, were you required to help with the family business?

Teresa: I was at the store from the time I entered high school.

Then I did what most of us did: we went to college and got an education. But when it came down to it, I made the decision to join the family business. I had studied accounting, but felt that type of work was not for me.I officially joined about 10 years ago to help my older sister, Diana, who had been running it with my older brother. He passed away about 10 years ago unexpectedly, so after much discussion, I decided to continue the family tradition, but more in a management role.

Andy: What prompted you to open another location north on Fraser Street at East Broadway?

Teresa: There has been much redevelopment up and down Kingsway. This location was sold to a developer a few years ago. Our lease ends in 2025, so the location on East Broadway was made in preparation for our departure. However, we wanted to stay in the Mt. Pleasant neighbourhood. The building at the corner of Fraser and Broadway is owned by the City of Vancouver and is home to the Vancouver Native Housing Society’s Kwayasut building, which is a supportive housing site for single adults and youths. We have a very good relationship with both the city and the Society.

Andy: Was there any hesitation at first to open the shop?

Teresa: My mom was reluctant at first and did not feel like she could go through with it. Fortunately, my dad encouraged her. Since day one, it was well received by the Vietnamese community, many of whom, until then, had not eaten bánh mì since they left Vietnam. In the early years, it became somewhat of a meeting spot for the Vietnamese community.

The journeys that these families undertook to escape Vietnam were not easy. It took extreme perseverance and a great deal of luck. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees estimated between 200,000 and 400,000 people who tried to escape after the war perished at sea. Worldwide, between 1975 and 1980, the intaking countries accepted approximately 800,000 refugees, with Canada taking in more than 120,000 of those. The adjustments required by these newcomers were difficult, but they all managed to establish a new life. In doing so, Canada received the benefits of their collective efforts, making Vietnamese food one of the most popular, especially in Vancouver. The Canadian government passed an act on April 23, 2015, declaring April 30 Journey to Freedom Day to commemorate the exodus of Vietnamese refugees and their acceptance into Canada.