Strategic Asset Management (Real Property)

Canadian Property Valuation Magazine

Search the Library Online

By Gordon E. MacNair, AACI, P. App., Director, Real Estate Partnerships & Development Office, City of Ottawa

Overview

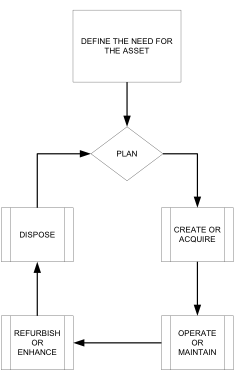

The purpose of this article is to review the complexities associated with real property asset management. The process begins with understanding the need and the owner’s objectives, planning, moving through the acquisition phase, the operation and maintenance phase, the refurbishment and enhancement phase, and, finally, the disposition of the asset. The article also explores the importance of having strategic professional staff oversee asset management on behalf of the ownership.

Asset management can be defined as the process of creating value within the owner’s objectives through the acquisition, use and disposal of real property assets. Alternatively, asset management is defined as the practice of maximizing the value of a portfolio of properties, within the objectives of the owner1.

While a real estate appraiser’s job is to place a value on the future benefits of a particular property, an asset manager has to realize those benefits. However, this article will demonstrate how the real estate appraiser assists the asset manager throughout the asset management cycle.

The process for asset management involves identifying the need and owner’s objectives for the requirement followed by five phases: planning, acquisition, operating and maintenance, refurbishment or enhancement, and, finally, disposal. This is illustrated in Figure 1 – The Phases of the Real Property Asset Life Cycle2.

As outlined in the text, Corporate Property Management: Aligning Real Estate with Business Strategy3 by Victoria Edwards and Louise Ellison, property is a ‘corporate asset’ and is held for one of two purposes:

- as an investment asset, or

- as an operational asset.

Property held as an investment asset, like any other investment asset, is expected to earn a rate of return on capital employed for the holder and, particularly in the case of freehold, appreciate in capital value. Property held as an operational asset serves to support the activities of the business occupying the property. This type of property is sometimes referred to as ‘corporate property.’

It is the author’s opinion that there is a difference between private and public sector real estate objectives. From a private perspective, the primary driver is financial, since, typically, there must be an acceptable return on the investment and capital appreciation (it is recognized that, with current market demand, environmental sustainability needs to be analyzed in order to address greening initiatives such as LEED, BOMA BESt, etc.). With the public sector, the objectives are broader and consist of the four pillars (financial, social, cultural, and environmental). As a result, it is a matter of balancing the various pillars to accomplish organizational objectives for the public sector asset manager. An example would be a large tract of land owned by the municipality, that has subdivision potential, but over half of the parcel is a woodlot, which has natural environmental features. In this instance, it is possible that the municipality would probably retain all or most of the woodlot to satisfy its environmental objectives. Clearly, the financial return would be greater by permitting housing development, but this would not allow the municipality to satisfy its environmental objectives.

Need for asset and ownership objectives

It is important to thoroughly understand the need, as this is incorporated within the owner’s objectives as demonstrated in Figure 1. The ownership objectives will vary widely among individual, corporate, fiduciary and government owners. In addition to the identification of specific assets that may align with any defined user need, it is also relevant to consider the application of an effective methodology, which will rationalize the acquisition of any asset and will ensure an appropriate and sustainable end-state property solution.

By definition, asset rationalization reduces the risk of improper acquisition.

Some owners see real estate as an investment, while others use real property for their own benefit and are interested in preserving the value of their investment. Most institutional and corporate investors have well defined, written goals in the form of policy statements or investment guidelines that are readily obtainable from their website. An example is Brookfield Properties4 which “is committed to building shareholder value by investing in premier quality office assets and pro-actively managing each of our properties to increase cash flows and maximize return on capital.” From a public perspective, the City of Ottawa is strategically driven to optimize the value of city-owned property holdings based on balancing the City’s financial, social, cultural, and environmental objectives for these holdings.

Planning

As John McMahan states in his book The Handbook of Commercial Real Estate Investing5, the role of the asset manager has evolved over the last 50 years, as real estate has gone from individual to institutional ownership and from the management of a few properties in a single market to large portfolios located in often dispersed geographical areas.

The modern real estate asset manager is a multi-disciplined, highly-trained real estate professional who is expected to not only be responsible for managing investment assets during the investment holding period, but be an integral part of both the acquisition and disposition process.

Below is a list of potential objectives for the asset manager as it applies to strategic asset management:

- support of corporate objectives, e.g., the four pillars approach (financial, social, cultural and environmental) through redevelopment or other initiatives;

- implementation of asset management strategies for all owned and leased facilities;

- provision of strategic portfolio planning and expert real estate advice to its ownership to ensure that their real estate needs are met in the most efficient and effective manner;

- generation of development strategies with intent to maximize the value of corporate real property holdings;

- development of effective property solution options for ownership that support a balanced and affordable solution;

- determination of the suitability and affordability of the portfolio to meet the needs of all client groups;

- development of value-added real estate solutions for core and non-core assets;

- development of facility and portfolio plans which recommend the disposition, remediation, redevelopment, retirement and/or retention of, and reinvestment in, those properties which are demonstrably sustainable, affordable and appropriately utilized; and

- analysis, rationalization, demonstration and communication of the accurate whole-life cost implications of real property solutions or policies that are introduced in response to the needs of clients.

Acquisition

The decision to purchase/lease real estate is found within the owner’s objectives. Some potential scenarios include:

- purchase of an existing property;

- purchase of a vacant site for development;

- redevelopment of an existing property; or

- lease.

With any acquisition, the buyer and seller ultimately enter into a Purchase and Sale Agreement (P & S Agreement). However, in some instances, a Letter of Intent may be prepared prior to this stage to outline the potential business terms. The P & S Agreement serves as a legal contract between the two parties and forms the basis for how the purchaser will obtain control of a property.

With the purchase of real property, proper due diligence must be carried out. Due diligence is the process of investigating and verifying information as it pertains to the subject property. Typically, this process starts before an offer is made. However, once an offer is made, it typically includes clauses that allow completion of further due diligence such as: title search, environmental investigation, building condition audit, designated substance profiling, engineering and structural reviews, etc.

The amount of time that a purchaser needs to satisfy due diligence requirements is a critical part of the negotiation process. Clearly, the transaction cannot close until the due diligence process has been completed.

Due diligence for a vacant parcel of land might include confirmation of zoning, official plan designation, satisfactory financing, obtaining an appraisal, title search, assessment of environmental issues, review of survey plan, consultation with the local municipality, determination of geotechnical condition of soil, private/municipal services, accessibility, review of future development in the area, development charges, off-site obligations, archaeological issues, wetland concerns, etc.

Similarly, the due diligence process for an improved property might include the above as well as a building condition audit; and review of: life cycle costs, historical operating costs, environmental issues within the building (mould or asbestos), copies of all leases (if an income producing property), any outstanding work orders, barrier free issues, code compliance, estoppel certificates for tenants, confirmation of chattels vs. fixtures, special local improvement charges, property taxes, confirmation of building permits, etc.

Whole-life costing

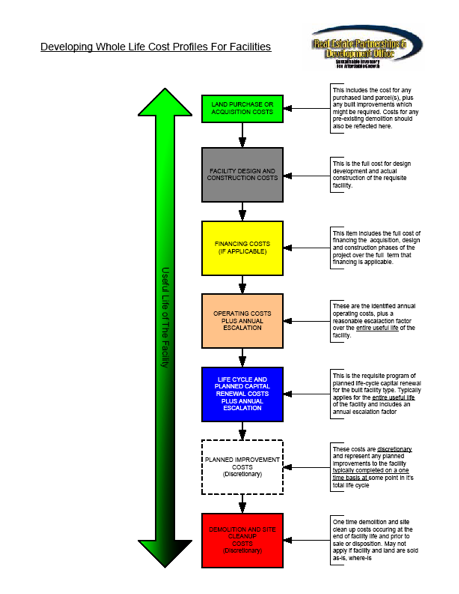

Whole-life costing6 is a key component in the economic appraisal associated with evaluating asset acquisition proposals. An economic appraisal is generally a broader based assessment, considering benefits and indirect or intangible costs as well as direct costs.

In this way, the whole-life costs and benefits of each option are considered and usually converted using discount rates into present-value costs and benefits. This results in a benefit-cost ratio for each option, usually compared to the ‘do-nothing’ counterfactual. Typically, the highest benefit-cost ratio option is chosen as the preferred option.

As part of this analysis, the cost of capital relative to business opportunity costs is an important consideration for the private sector, and could result in choosing another option such as leasing. With respect to the public sector, this would be balanced with the four pillars approach and it is also recognized that the cost of capital is less than the private sector.

The whole-life costing model includes for the periodic lifecycle (capital) replacement of major components and systems, which, in turn, establish the cradle to grave requirement for measuring and managing a physical asset’s useful life. A whole-life costing model can assist in determining the true value of any leveraging opportunity and to ensure the proper balance of risk and opportunity in structuring any leveraging arrangement.

Simply put, whole-life costing is analyzing the ‘true cost of ownership.’ This is demonstrated with Figure 2 – Developing Whole-Life Cost Profiles for Facilities:

Operation/maintenance

At this stage property management professionals who are responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations typically maintain the property. Examples include: custodial services, maintenance and dealing with tenants.

At a more strategic level, the ownership will require a business plan for each property, which requires an ongoing review of the real property inventory; it also requires financial reporting to the ownership on a regular basis.

As part of any effective asset management plan, an accurate inventory is required to describe all real property assets. The inventory database should be updated on a continuous basis. In addition, an inventory review should include a review of all leases or lease abstracts, rents, operating costs, lease rollovers, tenant relocation, additional rights such as a First Right of Refusal or Right to Purchase, etc.

In some instances, real property assets can be categorized in the following classes:

- Core properties are primarily used to accomplish the operational purposes or service-delivery objectives, which could include improved properties and/or vacant land, and

- Non-core assets, which are functionally obsolete, near or at the end of their economic life, and could be considered as surplus or underutilized. Non-core assets are those properties that are considered to be excess to the corporate mission.

Benchmarking and performance measurement

As part of any effective asset management plan, balanced performance measures must be in place to ensure that you are being competitive within the marketplace. Benchmarking is a form of measurement based on a continuous improvement process that can be compared and measured. This could result in outsourcing/insourcing of various functions such as janitorial services, property management, etc.

Refurbishment or enhancement

This stage includes a review of the owner’s objectives relative to the current market conditions and, completion of a cost-benefit analysis by the asset manager. Once completed, one or more of the following analytical tools can be used:

– Net present value (NPV)

– Internal rate of return (IRR)

– Return on investment (ROI)

The above analysis may result in several scenarios such as:

- status quo,

- initiation of a change of use due to a highest and best use analysis,

- modernization/renovation of the property, and

- disposition.

For additional information on strategic asset planning, reference the objectives of an asset manager as outlined under the Planning phase.

Disposal

Factors that may contribute to an owner’s decision to sell include:

– seller’s market,

– improvements are at the end of their economic life,

– major life-cycle work,

– change in ownership strategy such as a lease to offer more flexibility, and

– need for cash or liquidity.

Similar to the acquisition phase, the ownership would typically complete its own due diligence analysis before the disposal. Some items that may be considered at this time are:

– commissioning an appraisal,

– confirmation of market conditions and business cycle,

– review of leases including rents and operating costs,

– obtainment of estoppel certificates,

– title search to ensure that there are no surprises,

– requirement for life-cycle work, and

– completing a Phase I Environmental Site Assessment.

The ownership must also determine whether or not they are prepared to sell the property ‘as is, where is’ or, alternatively, what warranties and representations they are prepared to accept. There could also be consideration as to whether or not there are any outstanding work orders or restrictions on title such as easements and covenants that would need to be addressed.

With respect to a marketing strategy, the type of property, market cycle, method of sale and geographic location are all examples of factors that require consideration. For commercial properties, potential purchasers will be interested in the tenant mix, quality of tenant and contract rents, which are all components of the ‘quantity’ and ‘quality’ of income.

There are a number of options that an owner can choose for disposal such as listing with a real estate broker, direct sale, auction and tender.

Conclusion

The primary focus of asset management is the creation of value to achieve owner objectives. In the real estate ownership cycle, this process begins with understanding the owner’s objectives, planning, and moving through the acquisition phase; it continues through the operation and maintenance phase, and the refurbishment and enhancement phase; and, finally, ends with the disposition of the asset. Due to the complexities of asset management, it is also important to have strategic professional staff overseeing this mandate on behalf of the ownership.

For additional information on asset management, the BOMI Institute offers a four-day course and the IRWA offers a one-day course.

References

1 Asset Management, BOMI Institute, Defining Real Estate Asset Management, pg. 1-2

2 Queensland Government Government of Works www.build.qld.gov.au/downloads/bpu/sam_overview.pdf

3 Corporate Property Management: Aligning Real Estate with Business Strategy, by Victoria Edwards and Louise Ellison, pg. 4

4 Brookfield Properties

http://investors.brookfieldproperties.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=91790&p=irol-irhome

5 The Handbook of Commercial Real Estate Investing, John McMahan, McGraw-Hill, 2006, pg. 164

6 Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whole-life_cost